Decoding Shavuot: From Revelation to Education

No one in my high school believed me that Shavuot existed. They knew Yom Kippur and Rosh Hashanah because school was cancelled, they’d at least seen a Sukkah and heard of a Seder, but when I said that I had to miss two days of school for “something called Shavuot” so that I could “go to shul” and “eat a lot of dairy,” I received dubious looks. My elderly photography teacher (who was also Jewish) fully thought I was making it up and threatened to lower my grade if I missed another photo critique for another Jewish holiday.

Why did so few people know what Shavuot was? Even in my 50-percent-Jewish-but-99-percent-nonreligious high school only my fellow day school transplants were familiar with the holiday. Part of Shavuot’s obscurity is related to its divergence from all other Jewish holidays: Shavuot is the only chag, holiday, with no specific mitzvot, commandments, prescribed to that holiday. Mitzvot give us a tangible way to experience and understand chagim. We remember Channukah for its channukiot, Sukkot for its sukkah, Shabbat for the challah and candles and wine. Mitzvot often use ritual objects, and these objects become a touchpoint, and ultimately a synecdoche, for the holiday. We created Shavuot minhagim, widely practiced customs, to combat the tension of a holiday without mitzvot, but the minhagim do not erase the conflict.

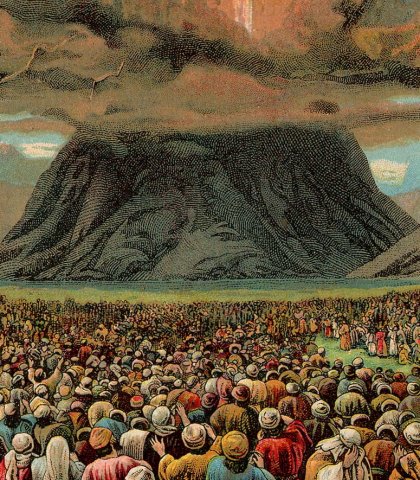

Shavuot’s tension is deepened by the holiday’s keystone - a mythic, remembered collective experience: the revelation. There is a rabbinic concept that all Jews, past and future, were present at Mount Sinai when the Torah was given. It’s markedly odd that a holiday with a collective experience at its theological epicenter doesn’t require any created, ritualized collective experiences in the form of mitzvot. Perhaps Shavuot emphasizes the importance of individually processing our collective experiences by focusing on the text of a collective experience but not giving us a ritualized way to understand it.

My bar mitzvah happened to be on the second day of Shavuot. Like most Ashkenazi-American bar mitzvah boys, I lained my parsha, wore a tallit given to me by my Bubbie and Zaidie, and wrote a d’var Torah. I also led Hallel and sat through Yizkor. Those differences from other Shabbat mornings did not make the day feel more special. Rather it was the sameness of experience that put me in conversation with Jewish tradition, and it was the fact that these things were finally happening to me that made the day feel special and particular to my own embodied experience. It was the process of individually undergoing a collective experience that made having a bar mitzvah valuable.

Jewish knowledge is transferred through ritual; we teach Judaism by teaching how to live Jewishly. Shavuot reminds us that we must allow space for individual understandings, even when the collective experience is central. Shavuot urges us to transfer the generational knowledge and collective experiences of Judaism to young Jews, but also asks us to give them the tools to figure Judaism out on their own terms. In our increasingly globalized and socially conscious world, it is of the utmost importance that collective experiences do not remain stagnant. They must change to fit whoever they need to, so that all Jews feel like they have a space in our shifting landscape and know that they too were there at Mount Sinai and witnessed the receiving of the Torah.

Josh Schwartz is a Project Associate for the New York Teen Initiative at The Jewish Education Project.